The pilot wasn’t sure where we were flying. Striding across the tarmac in his green flight suit he checked the paperwork in his hand, nodded, and confirmed we’d be sticking to the plan: Cape Romanzof, a rocky slice of tundra pressed between a volcano and the mouth of the Yukon River where it thunders into the Bering Sea. Romanzof is home to a secret-but-not-too-secret military radar, and after nine months of coordinating with the Air Force I was walking to the plane for a visit. The trip is 532 miles by air – about two hours in the small plane. We’d be on the ground for three hours before doubling back to Anchorage. Weather permitting.

In the American cartographic imagination, Russia is on the opposite side of the rectangle. If you measure from Washington D.C. to Moscow this is true. But in Alaska, there really are places where, on a clear day, a person can look out the window and see Russian islands – even the mainland.

This proximity is one of the reasons Alaska exists. Abundant and thinly populated land at the top of the world became staging grounds for American soldiers who could quickly be sent around the world. Likewise, the poles became a vantage point in anticipation of a sneak-attack through the attic.

The resulting Distant Early Warning system, or DEW Line, a class of high-tech monitoring stations set up in the 1950s, spans across Alaska from Kaktovik to Shemya, 15 sites just in Alaska, a few more scattered as far as Wake Island in the Pacific. The military made different perimeters monitored by radars meant to spot long-range bombers or missiles heading toward the U.S. and Canada while there was still a chance of taking action, whether that meant scrambling jet-fighters or ducking-and-covering under a school desk.

They looked like the experimental compound you’d build to practice colonizing the moon.

Building, engineering, and staffing these sites in some of the most remote, harsh environments in the world was a massively ambitious Cold War undertaking by the military. It involved dropping some of the most sophisticated instruments of the day into places where they’d almost certainly be destroyed. To keep them humming, the military conscripted underqualified airmen from temperate biomes to babysit the machinery and shovel snow off the roads at -40 degrees. The program spent massive amounts of money and effort in the name of preparedness: getting eyes and ears on our Soviet neighbors right by the backyard fence of the Bering Strait.

The Long Range Radar site at Cape Romanzof is 532 miles from Anchorage at the edge of the Bering Sea.

Many of these original radar sites are still here. For a civilian like me, getting there meant a lot of goodwill from public affairs officers, months of emails, and a seat on an Air Force plane during a Lieutenant Colonel’s routine inspection visit.

We hung out in the air for a while, burning fuel as the pilots waited for an opening in the cloud ceiling to drop through. When they got it, we glided in low over choppy water toward a barebones airstrip, setting down lightly.

Waiting by a pickup truck in a light drizzle, Bradley Hinds warmly greeted crew members from our flight. He was our ride. Some of the Air Force guys from my flight scampered up to a sign welcoming visitors to the Cape Romonzof Long Range Radar Site, posing for trophy pictures.

The residential and equipment domes at Romanzof, where the few residential technicians sleep, eat, and recreate. Up above is the top-site, where the radar is situated. The domes are insulated with a synthetic orange foam. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

Hinds is a maintenance contractor at Romanzof. As we drove away from the airstrip, he gave us a tour built not on local sights so much as daily duties. One of his main tasks is keeping clear the several miles of dirt road. During a winter storm, that means eight to 14 hours of plowing snow a day, often eight to ten feet deep.

The entirety of the Romanzof site is made up of three distinct areas: a giant white golf-ball on a hill where the radar and its accoutrements live; far below are two looming orange domes encircled by a geometry of storage containers; and below that is the airstrip, the gateway for supplies, visitors, and escape. From up above, the roads looked like loose twine tying all the pieces together.

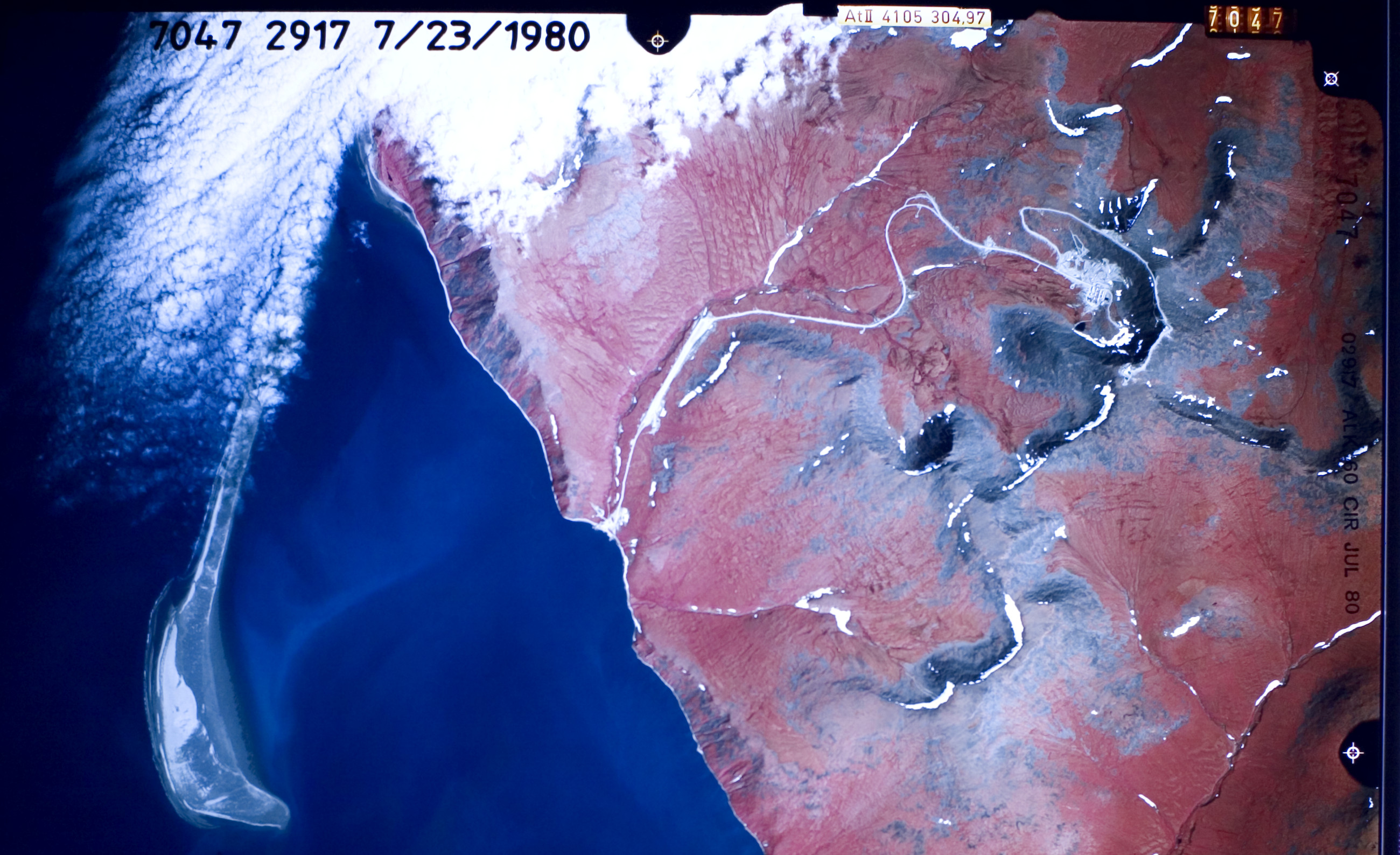

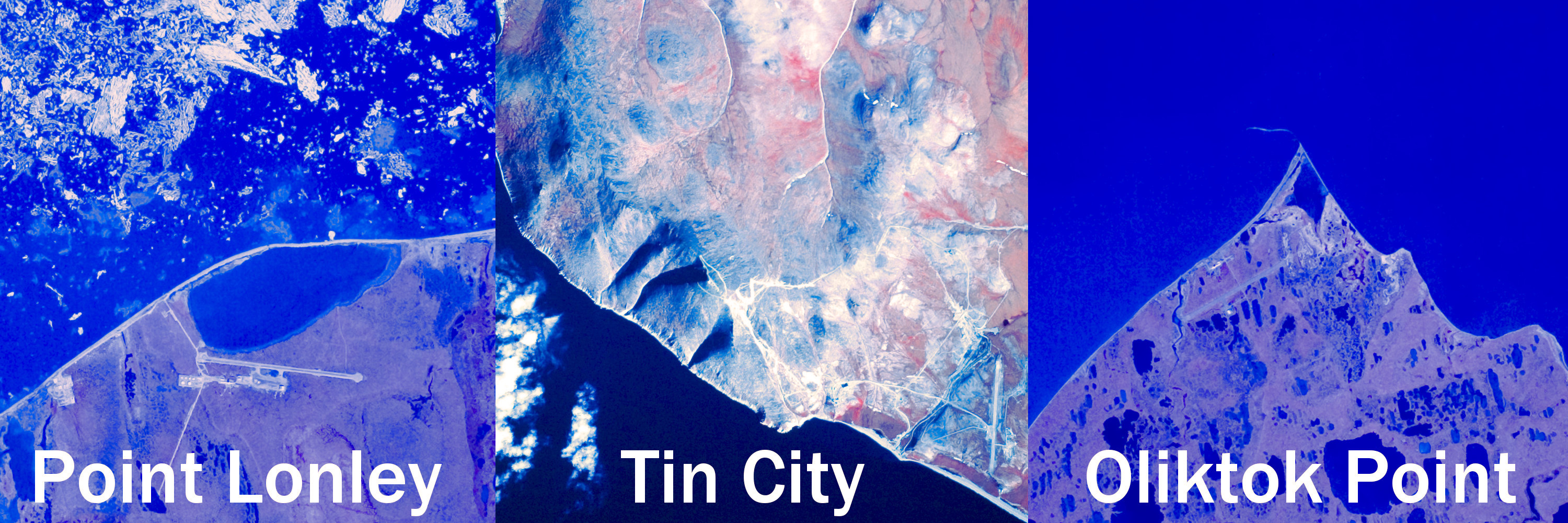

The Romanzof site, seen from above. The long, straight line on the left is the airstrip, connected by a long ribbon of road to the cluster of residential and equipment buildings. Up an elevated climb looping around to the top the defunct volcano is the actual radar building. Photo from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center.

As the truck trundled over mud and rocks, the globular curve of those two orange domes creeped up out of the horizon’s otherwise earthy color pallet.

“That’s the vehicle shed and the residential dome,” Hinds said. “It’s where we live.”

They looked like the experimental compound you’d build to practice colonizing the moon.

We stopped briefly outside the dome home to change trucks, and met our next chaperone: Max Jones, a stocky guy with eyes that looked at once intelligent yet slightly bored.

“This is Cape Romanzof weather,” he said of the shifting gray precipitation. It was late June and the temperature was in the fifties. Now and again, unmelted pockets of snow would appear in hillside nooks.

“We have a saying: come ‘cause you have to, stay because the weather won’t let you out,” Max said.

The road was steep, with sharp turns every few dozen feet and tracts of thick mud that jolt the cab each time a wheel lost its grip. As we climbed, thick fog surrounded the vehicle, making it impossible to see even a few feet behind us, where another truck followed along.

“Lotta times in the winter I can’t see beyond eight feet, hafta to open the door and use the side of the road as my gauge,” Max said dryly.

Abundant and thinly populated land at the top of the world became staging grounds for American soldiers who could quickly be sent around the world. Likewise, the poles became a vantage point in anticipation of a sneak-attack through the attic.

As the grade got steeper, the fog denser, it began feeling like if we miss one of the hairpin turns the truck would just lurch over the edge of the cliff. I knew my job was to ask Max as many questions as I could, but I grew terrified of dividing his attention in any way. What if he turned his head to be polite and our wheel slid into a crumbling nook of pebbles? The only thing that kept me from full-on hyperventilating was how totally chill Max remained. One hand on the shifter, the other slouched over the steering wheel, like this was any old back-country road. I worked up the courage to ask another question.

“I can’t see, but are these sheer faces?”

“Yeah, it’s an old volcano, it’s 3,200 feet straight down right there,” Max said matter-of-factly.

An Alaska National Guardsmen monitoring radar data inside the Regional Air Operations Command, a windowless facility at Joint-Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

It’s no accident the radar is on the side of a volcano. When sites like this were built in the 1950s, the military selected locations were selected for a combination of remoteness, elevation, and weather conditions. Military planners didn’t want the Soviets to know where these sophisticated alarm bells were positioned. Not only were they in the middle of nowhere, but precipitous, difficult weather was considered an asset: another layer of cover. This, however, sucked for anyone forced to live on the ground, beneath all the clouds and wind.

Through policy, the military acknowledged the danger, cold, and loneliness of these sites. Radar deployments were considered hardship postings: rotations lasted just a just a single year, instead of the customary three in Alaska. The only connection to the outside world were mail planes. But even they were frequently weathered out.

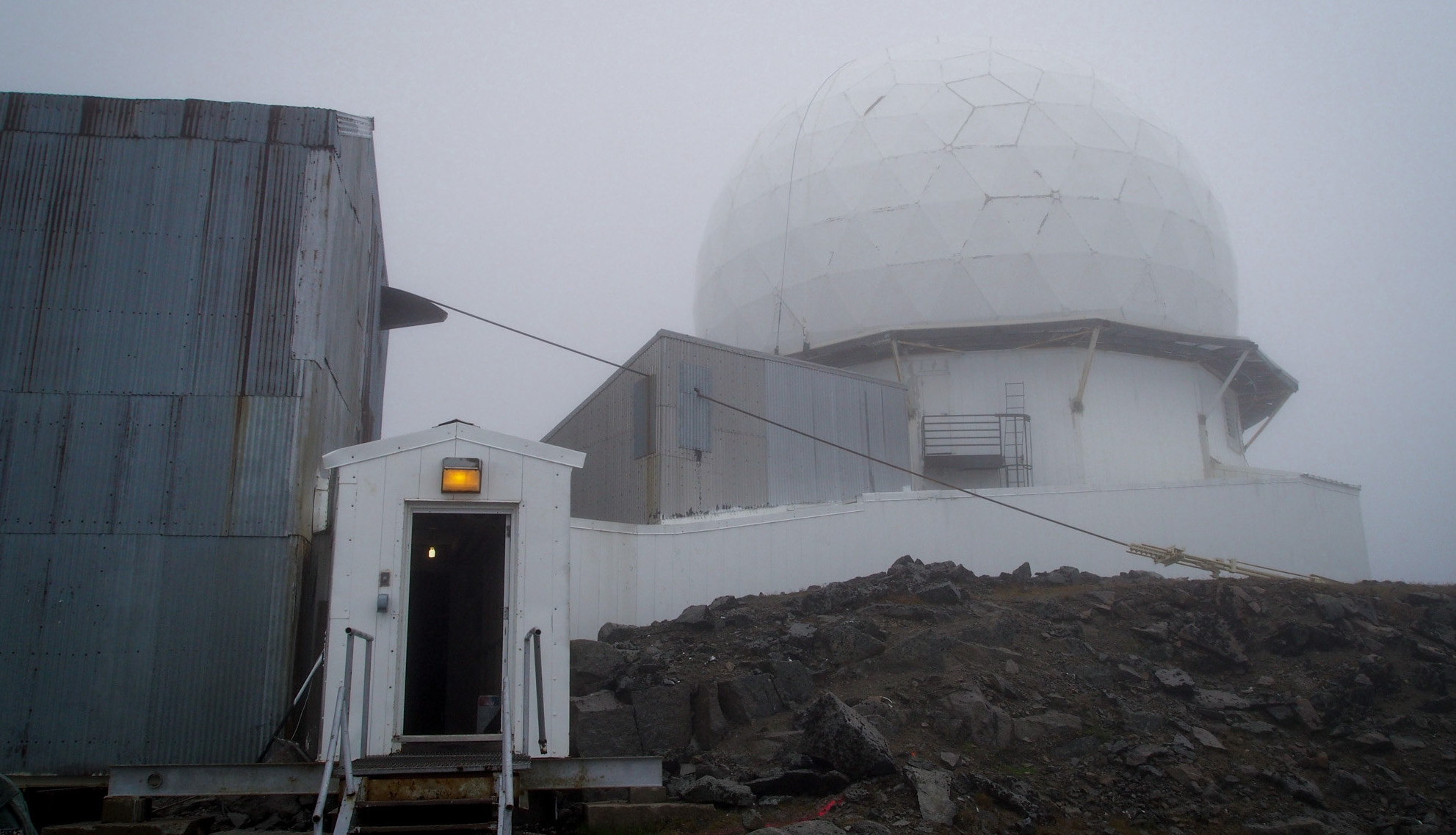

The radar at Romanzof, is protected beneath a geodesic cover to keep the equipment safe from the elements. Variable and obscuring weather was considered an asset in site selection, along with good elevation, when the radars were being build during the Cold War. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Long Range Radar sites required hundreds of Air Force personnel: People to cook, clean, fix machinery, watch the radar screens. At its peak, Romanzof was home to 280 people. In old photos, young guys in bomber jackets and buzz-cuts staring morosely at empty radar terminals, exhibiting the kind of pathological boredom airmen bemoaned in letters home.

The Air Force did its best to dilute the tedium, building bowling alleys, movie theaters, even ski lifts, something of a summer camp by the sea ice. There were no women or families at the sites. Rooms were spare. Though efforts were made to keep people from mental and physical collapse, there was no delusion one could live anything but a simulacra of normal life.

“After dinner it was each man to his own pleasure,” intones an announcer for the Western Electric Company from a half-hour documercial released in 1958 called “DEW Line Story.” “Perhaps you preferred a rousing game of table-tennis -- no quarter given. Or there was that other fine intellectual past-time called poker. No quarter given here, either.”

Other Long Range Radar sites in Western and Northern Alaska. Photos from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center.

A lot of the fun stuff has been ripped out and hauled away since the sites were turned over to private contractors beginning in the seventies, the footprint of each installation on the land reduced, and reduced, and reduced. Until now, Arctec, the current contractor for all the LRRs in Alaska, has just four employees to keep the radar spinning at Romanzof. Barely enough for a decent poker game.

You’d think it’d be lonely, boring, depressing. But Max doesn’t see it that way.

“I did 20 years in the Navy, being out on a remote site doesn’t bother me,” he said. “But it’s not for everybody.”

85 percent of people employed by Arctec at LRR sites are ex-military, many already trained in the equipment and protocols. Max used to handle weapons systems onboard ships; that involved a lot of radars like the one we were approaching.

I’d figured most of the techs came here after penciling out a shrewd calculus about how long they could last for maximum profitability. I expected the kind of gruff, enduring grunts of a for-profit penal colony, but Max described it as “probably the best job I’ve ever had.”

“There’s so much variety,” he added. “No two days are ever the same.”

In the winters contractors spend as many as 14 hours a day keeping roads linking the air strip and radar clear of snow. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

The gig lets Max do an array of work that keeps him from getting bored with repetition or dull from specialization. Tinker with sensitive military equipment Tuesday, plow snow off the edge of a volcano Wednesday. Who knows what Thursday will bring?

It’s also good money. A manager for Arctec, Kevin Smiley, told me a technician in Max’s position gets a salary in the area of $140,000 before overtime, of which there is plenty.

But still: you have to be willing to leave your home for months at a time, living in a kind of busy yet anti-social environment that most people would have trouble coping with. According to Smiley, Arctec screens for this. Nowadays techs are picked in part because they can stand the solitude. Max recalled being asked during the interview phase whether he had a problem working at remote sites.

“They don’t hire people who realize they can’t handle the isolation,” Max said, turning off the ignition and opening the truck door in the same motion.

We’d arrived at the top of the hill, an unremarkable dirt knoll loomed over by the giant golf ball. Everyone spilled out of the trucks.

The golf ball is really a geodesic sort of scrim to protect the actual radar from the elements. Beneath the orb is a rusty shack made of cheap looking metal. It housed the now-retired tram system people once used to commute between the radar and the residential lower site. The mere idea of ascending several thousand feet in an antique ski-lift is the only thing more terrifying to me than the drive we just did.

We entered through a metal door flanked by broken handrails. At the end of the elongated foyer Max paused to impart a few rules.

“You’re ‘bout to enter a restricted area. I’ll be your escort,” he half recited. “I gotta have eye contact with the civilian guys the whole time.”

We had to leave cameras and cell phones outside, but I was allowed to keep my audio recorder. From the second Max opened the door, a weird hum started hitting the microphone. I could hear it in my headphones, but not my naked ears. It was a frail whine, perhaps the aural manifestation of a radiation I didn’t know to avoid. I fretted for the health of my spleen and innards.

I was expecting the Bridge from Star Trek, but the giant room full of sensitive military equipment was far duller. Like the basement of a fax machine company. We even had to register on an official ledger, a sort of government issued guest book.

The remnants of a tram system are still at the radar top-site at Romanzof. At some sites, the tram is the only way to access the radar for maintenance and inspections during the winter, which can cause technicians to be stuck there for weeks at a time when equipment malfunctions. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

Max gave us a tour, but truthfully, the technical particulars went over my head. All around us was non-descript machinery resembling refrigerators, filing cabinets, and fire-proof safes that I was assured were crucial to national security. And yet it was the happiest I saw Max in the whole course of my visit.

“This whole office belongs to me,” Max beamed, before launching into an explanation of a gray metal box.

My eyes wandered to something I could actually relate to: a toilet inside a closet. Tucked off to the side the donut-shaped room was an efficiency apartment designed to a shelter a tech should they get stranded up at the top camp. It was summer, so the risk of this happening was low. The main provision left on a countertop was half a case of Cambell’s soup.

But the strandings are not theoretical. One happened the previous winter at a sight called Tin City, notorious for dicey weather on the tip of the Seward Peninsula across the thin Bering Strait from the Eastern shores of Russia.

All around us was non-descript machinery resembling refrigerators, filing cabinets, and fire-proof safes that I was assured were crucial to national security.

“A tech got stuck up there for two weeks,” Max explained. In the winter, the tram is the only way to get up to the radar for maintenance checks.

Except in this instance the culprit wasn’t weather, but the rickety Eisenhower-era jalopy tram.

“They couldn’t run the piston-pulley up and down the mountain,” Max went on. “They took him up, dropped him off, and it broke on the way back up.”

By the time they were able to fly parts out and fix the machinery a fortnight had gone by for a solitary technician, dozens of miles from any sizable community and another several thousand feet from any other human. Eating soup and shitting in an incinerator toilet.

By now we’d gotten to the second floor, which had a prominent hole in the center of the room, the dark innards of the golf ball.

A faint view of the lower site from the radar station atop a defunct volcano. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

“That’s the mission,” Max said, pointing into the void. “Everybody out here is to support the thing that’s spinning around over your head.”

All the techs and military guys got a hint of reverence in their voices explaining the real, actual, physical radar up above us -- the shrine around which this whole remote temple is built.

“You see that wagon wheel turning?” Max asked. “That’s the radar turning.”

It was too dark inside the golf-ball for me to make out details. I could see a play of shadows as the radar’s long strips of metal rotated in even circles. For all the money and effort it takes to keep this machine running, in that moment I wished it were more impressive. Instead, it reminded me of staring at a ceiling fan when you can’t fall asleep.

Amid the quiet spin, though, the wagon wheel invisibly sends out pulses that move a mile in twelve millionths of a second, speeds that are physically possible but mentally un-graspable, meaningless but for the impression of awe.

It probes the sky 250 miles in every direction, creating a macro-visibility no eye or telescope could glimpse. It’s looking for bombers, for planes that have veered far off-course, for threats and foreign objects.

But amid the quiet spin it invisibly sends out pulses that move a mile in 12 millionths of a second -- speeds that are physically possible, but mentally un-graspable. It probes the sky 250 miles in every direction, creating a macro-visibility no eye or telescope could glimpse. It’s looking for bombers, for planes that have veered far off-course, for threats and foreign objects. But more often it picks up the happenstance of the sky: clouds, small commuter flights, even flocks of migratory birds.

We took a last look before retracing our steps to the trucks. The techs got them warmed up, then poked around the perimeter of the building to inspect a few last things.

Our group headed back down the road. We peeked into a heavy-equipment shed, which housed to a massive front-loader for rearranging earth and snow. But I was eager to get back to the dome homes and see how they functioned. Behind Max Jones and the array of fancy military technology is a range of equipment less exotic, but just as important. Refrigerators for food, DVD players for entertainment, small bedrooms for rest. Though the techs are constantly at a work site, they also live here. And while it’s tough, they aren’t exactly toughing it.

The domes are the site of all the labor it takes to keep a radar technician fed and rested enough to focus singularly on maintenance and engineering tasks for the majority of his waking hours. And that labor is not treated as peripheral, but essential to the mission. Residential techs wield authority over the home and hearth same as Max and Bradley Hinds do over their snow plows and anonymous metal boxes.

At Romanzof, these responsibilities are vested in an energetic grandmother.

“How ya doin’ darlin!” hailed Leta Page from the edge of her kitchen, bearing an apron, baseball cap, and smart remark.

Earlier in the day, Leta had laid out an elaborate lunch spread for unusually chaotic day at the dome. Though there are normally only about four people at Romanzof, the site was hosting 20 seasonal environmental workers. Arctec had flown out a backup chef to assist Leta, who was essentially in charge of feeding a football team three times a day.

In metal cafeteria trays were heaps of corn chowder, vegetable lo mein, mac’n’cheese, beer battered halibut, and several healthy-looking but unidentifiable salads. Machine-made coffee and Styrofoam cups occupied a corner near the soda fountain. In a freezer were ice cream bars for dessert.

After everyone ate, the leftovers were put away, and the industrial kitchen wiped down, Leta showed me around, beginning with a tour of her various walk-in freezers.

“I keep my cheeses here,” Leta said with a wave.

“How much bacon is that?” I asked of a large mound piled in a box.

“They’re about 20 pound lots,” she replied, referring to each packaged unit. There were several lots. “These guys eat a lot of bacon.”

In fact, this wasn’t even all the bacon cached at Romanzof; more storage freezers hummed upstairs. The kitchen where we stood was only for food set to be eaten in the near-future. And given our location, hundreds miles from anything resembling a temperate growing environment, there was a respectable variety of leafy green produce.

“We have celery, and avocados, and broccoli,” Leta pointed. “All the normal normals.”

In her affect and duties, Leta was somewhere between an Army quartermaster and the owner of a Bed and Breakfast in one of the cozier states, like Vermont. She sends Arctec shopping lists of all the things she needs, and every three weeks they send her back a plane loaded up with groceries. Weather permitting. There’s actually enough food on site to last for months, although the further along you get the more of it comes out of cans and the back of the freezer.

These contingencies are not hypothetical. In the past Leta has gone a month-and-a-half without a plane being able to make it in.

“We didn’t have anything fresh,” she recalled. “I had frozen stuff.”

She joked that if her dome-mates wanted fresh milk during that lull, she told them to go milk the cows. (Note: there is no livestock at Romanzof). If they wanted eggs, she sent them to raid the seagull nests down by the beach.

“You become very creative,” she said with a nod. I assumed this was a joke, too, but you can’t quite tell with Leta.

We left the kitchen, walking through the octagonal dining area filled with laminated wooden tables arranged within view of a large flat-screen TV on the wall. Along the perimeter were side rooms for supplies, spare accommodations, and a bathroom with a sign reading, “You mother doesn’t work here. So clean up after yourself!!”

Vines dangled from a banister on the second-floor balcony, the leafy appendages of spider plants, creepers, and bamboo. Some of the plants pre-dated Leta, but others she’d brought out with her, explaining mischievously she’d traded the receptionist at a dentist’s office old magazines for cuttings to transport.

“It’s good for you,” Leta explained of her modest indoor garden. “I gotta breathe this air.”

A persistent rumor about the radar sites is that the techs are fed lavishly, with regular steak and lobster dinners to induce occupational fidelity in a challenging locality. This is a misperception Arctec is understandably eager to dispel; it would be bad form to spend taxpayer money flying lobster tails to the Arctic. But the rumor is mostly untrue. Kevin Smiley, the Arctec representative in charge of managing the technicians, said it’s only on special occasions that employees are treated to a menu of special options. For the holidays, Leta and her colleagues in the dome got to pick out items like crab legs or shrimp. But most of the time, everyone at Romanzof is at the gastronomic mercy of Leta, who embraces a my-way-or-the-highway approach to meals.

An Air Force pilot of a C-12 flies from Elmendorf to Cape Romanzof. Photo: Zachariah Hughes.

Crossing over into the second dome was like stepping into a Home Depot. Cement floors, glaring lights, and metal racks filled with every possible supply you could need. It made me want to drive a forklift.

“Sometimes we don’t get a plane in for quite a while,” Leta said of the stockpile shelved before us. “Then people like me are hoarders.”

The techs need to have a spare part for every possible thing that could break. The nearest village is 15 miles away by boat or snowmachine, which in bad weather might as well be another country. There was a spare generator, rows of paint cans, and the carcass of a washing machine that could still be scavenged for a few parts. There was even an extra eye-wash station resting against a shelf.

The well-appointed warehouse gave Leta no small amount of pleasure. She guided me on a brief tour of mattresses, rugs, and extra chairs with an exuberance usually reserved for describing how you grabbed the last toy on the shelf a day before Christmas.

“Back behind here I’ve got blinds for the windows,” Leta said with impish glee.

There’s more food and material cached in this private dome than in entire stores I’ve visited in rural villages. Those might serve several hundred residents. The bounty around us is for just several people. There’s a section in my notes from this point in the trip that reads simply, “There’s just so much stuff.”

You can’t stream Netflix at Romanzof. Since the fifties, the Air Force has flown out books, magazines, and movies from a library on base. That’s evolved into a media-room with DVD’s, a Nintendo Wii, and a popcorn machine that Leta bought herself.

“It breaks up the monotony,” she said.

The internet quality is decent enough for Facebook and phone-calls, and so Leta and the other techs are able to stay in consistent communication with family. They are not in silent exile. In fact, I get the sense Leta is like a lot of grandmothers who subsist on communicating digitally with their grandkids until they can squeeze them in real life. For Leta, that happens about every three months, when she rotates off site for about a month at a time. She owns a house in Anchorage, and when she talks about it she says she “lives” there -- a term that feels a little odd, given she spends three-quarters of the year in a glorified communal yurt hundreds of miles away.

Her resume with remote sites started years ago, when she worked on the distant Aleutian island of Shemya. She moved back into Anchorage when her husband got sick and eventually passed. Then, not long after, she put in an application with Arctec. Like Max Jones, Leta shrugged off any suggestion her job was exceptionally solitary or difficult.

“We don’t really need each other,” she said of her dome colleagues. “I don’t need them to entertain me, and they don’t need me to entertain them.”

It’s a community of loners. They join for meals, a few activities, but mostly everyone here is able to take care of themselves.

This is mission-driven work. Partly in the grand sense. Leta and everyone else I talked with at the site mentioned their role in national security. It’s a big-picture justification I don’t think you’d get if you were doing the same cooking and snow-plowing in the normal world.

Much quicker than I expected, it was time to go. Clouds had rolled in, and the Air Force pilots wanted to leave soon, lest we risk getting stuck for the night. As much as I wanted to stay, there was a colonel who needed to get back to base in Anchorage, and he was my ride. We jumped into a pickup, sped down the muddy road, and got ready to take off.

In spite of the great mass of technology plopped on the edge of a defunct volcano, none of the staff here actually know what the radar is picking up. Instead, the data is beamed back to Anchorage, where a small platoon of service-members sit at office chairs in a windowless room deciphering colorful dots projected on digital maps. The radar itself is just an eyeball, not the brain interpreting images and deciding what to do with them.

A few times a year, Russian jets will fly over international airspace toward the U.S. Their aim is to see how long it takes the military in Alaska to get permission from far-away commanders to launch F-22 fighter planes in response. It’s a cat-and-mouse game: testing how fast your opponent can react. It was described to me as routine, and often, with a smirking sense of humor, happens on national holidays.

Before departing the radar top-site, I’d walked away from the group a bit, down the road toward the thick bank of fog. In the fog, there was no sound but the wind. It’s a strange feeling, knowing that in the middle of the quiet, chill air are the silent vibrations of a vast machinery. A whole system of nerve endings probing the sky for sensation and pulsing deep signals to a distant brain.

Photography by Zachariah Hughes. Web design by Ben Matheson. Hook image via Mourad Mokrane, Creative Commons.